Why did the Boston Tea Party Occur? Who was involved? We cover these facts and more on this page on one of the most momentous events of the American Revolution.

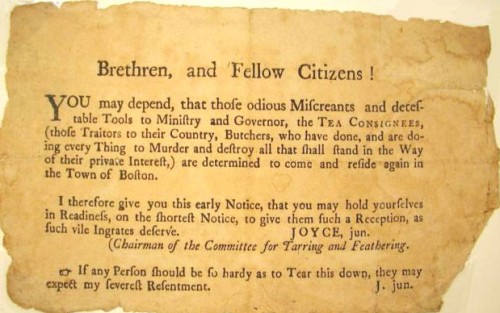

The broadside below was posted all over Boston on November 29, 1773, shortly after the arrival of three ships carrying tea owned by the East India Company.

This is the original handbill that was passed out to organize the Boston Tea Party. It reads …

| Brethren, and Fellow Citizens!You may depend, that those odious Miscreants and detestable Tools to Ministry and Governor, the TEA CONSIGNEES, (those traitors to their Country, Butchers, who have done, and are doing every Thing to Murder and destroy all that shall stand in the Way of their private Interest,) are determined to come and reside again in the Town of Boston.I therefore give you this early Notice, that you may hold yourselves in Readiness, on the shortest Notice, to give them such a Reception, as such vile Ingrates deserve.JOYCE, jun. (Chairman of the Committee for Tarring and Feathering.)If any Person should be so hardy as to Tear this down, they may expect my severest Resentment.J. jun. |

Why Did the Boston Tea Party Occur?

The beginning of the the Boston Tea Party is often sourced to what the Colonists felt was an unfair tax on tea. This is only partly true. The Tea Party was a protest in reaction to a tax meant to help raise funds following the French and Indian War. But the tax was also a political power move on behalf of Parliament, meant to reassert control over the colonies, as well as an economic decision designed to bail out the floundering East India Company, a threshold of English commercial interests.

Background

After the long and costly war between France and England, King George III and the British Parliament implemented a tax to help raise money to pay off the massive debts incurred. They chose to place this tax on tea sold in both England and in the English Colonies. They were convinced that people would rather pay a tax than give up their daily tea. It was also an item that the colonies were required to import only from England. Furthermore, the tax was a way to reign in the colonies, who had been neglected during the long war, and remind them that their allegiance belonged to England.

This Sugar Act was passed in 1764 imposing customs duties on several different items, including tea. Prime Minister Grenville wanted to raise the revenue by putting a direct tax on the colonists instead of at the ports, so he delayed to give the colonists a chance to find a way to raise funds themselves. They didn’t.

The following year, the Stamp Act was passed. All official documents and papers were required to have an official stamp. The cost of this stamp went directly to the crown.

The colonists were outraged. They complained bitterly that because of their distance from England, they were receiving inadequate representation in Parliament. They had not agreed to have these new taxes placed on their colonies.

The Stamp Act was eventually repealed, but not before the Sons of Liberty had formed and begun to perform public demonstrations and boycott, sometimes with violence and looting. The Colonists were frustrated by the number of taxes Parliament kept trying to place on them without their consent.

In 1767, the Townshend Acts rocked the colonies when they replaced the Stamp Act with an import duty on all kinds of essential goods. Parliament mistakenly thought the colonies objected to only internal taxes or purchases like the objects described in the Stamp Act, and that import taxes wouldn’t be a problem.

Parliament then offered a monopoly on tea importation to the colonies to the East India Company, who in turn raised their price on tea. The tea sold in the colonies wouldn’t have a tax any more, instead it would be taxed at each individual port, and agents were appointed to receive and sell the tea and pay the tax.

This was the Tea Act, passed by the British parliament on May 10, 1773. This was an attempt by the British government to prop up the failing Dutch East India Company. It reduced taxes and removed all duties on the exportation of East India Company tea. However, even when the tea tax was lowered with the Indemnity Act, the colonists protested, not because of the price, but on the principle that they were not required to pay taxes placed on them without their consent.

It’s often overlooked that the people in England were under the same laws and taxes and were smuggling tea, even more than the American Colonies were. The thing that upset the colonists the most was they felt they were unrepresented, unheard, and exploited by an “evil” Parliament.

When the taxes weren’t removed, some of the colonists made a small fortune on smuggled tea, including John Hancock. When the smuggling didn’t stop and neither did the violence caused by the Sons of Liberty, British troops were deployed to Boston.

Their presence was unwelcome and only added to the hostility the colonists were feeling against the crown. The hostility rose until it came to a head with the inaccurately named Boston Massacre when five people died. This was used as propaganda in the newspapers, fostering the unrest and increasing the tension.

The colonists were convinced that these Acts were an attempt to undermine colonial businesses. Nor were they in a compromising mood. They were angry over the Boston Massacre. Most of them stopped drinking tea altogether because while the Townshend Acts had been rescinded earlier in the year, its duties on tea were still in force.

Britain dropped the price of tea until the smuggled tea was actually more expensive than the regular tea. Those who were making a profit on smuggled tea continued to do so, but now it became less about saving money, and more in the name of protest for the colonists’ rights to “taxation without representation.”

In New York and Philadelphia, the colonists refused to let the boats land, and they returned to England. In Charleston, protests were so rampant that customs officials were able to seize all the tea.

In 1772, the Indemnity Act dropping the price on tea expired, and left the Townshend tax on tea. Consumers faltered at the sudden jump in the price of tea, but the East India Company continued to import it. Even though the company was failing, Parliament refused to back down regarding their right to tax the colonies. Furthermore, this tax paid the salaries of Parliament-appointed government officials, and they were loathe to allow those officials to be reliant on the colonists for their salaries, for fear it would drive them to be more supportive of their cause.

The Tea Party

The biggest shipment arrived in Griffin’s wharf, in Boston on or just before November 29, 1773.

The royal governor Thomas Hutchinson had no intention of letting the colonists force the ships to return to England, and due to the Boycott, the dockworkers refused to unload the ship. He held the ships in port, demanding that the cargo be unloaded and customs duties paid.

But the colonists, already stirred to action, were unwilling to bear the stalemate.

On December 16, “there was a meeting of the citizens of the county of Suffolk, convened at one of the churches in Boston, for the purpose of consulting on what measures might be considered expedient to prevent the landing of the tea, or secure the people from the collection of the duty. At that meeting a committee was appointed to wait on Governor Hutchinson, and request him to inform them whether he would take any measures to satisfy the people on the object of the meeting.”1

The Governor promised an answer by 5 pm, but when the appointed time came, the committee met at the Governor’s house, and he was missing.”Let every man do his duty, and be true to his country,”2 cried the members and dissolved the meeting.

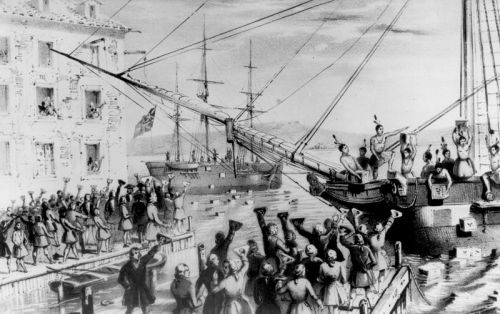

Boston Tea Party picture by Sarony and Major, 1846 | Public domain image

The Events of the Boston Tea Party

That night, over 100 men including the Sons of Liberty dressed in “Indian” garb, or rather, the poncho and soot streaks soldiers wore during the French and Indian War. They armed themselves with hatchets, axes, and pistols, and sneaked aboard the ships.

Accounts actually vary from 30 to 130. Bostonteapartyship.com maintains a list of 116 names culled from various historical reports.

An observer of the Boston Tea Party, John Andrews wrote the following in 1773:

| They say the actors were Indians… Whether they were or not to a transient observer they appear’d as such, being cloth’d in blankets with the heads muffled and copper color’d countenances, each being arm’d with a hatchet or ax, and pair pistols, nor was their dialect different from what I conceive these geniusses to speak, as their jargon was unintelligible to all but themselves. 3 |

Three ships with their cargo of precious teas lay in Boston harbor, their captains unaware of the colonists’ approach.

The clothing was both to keep their identities hidden (because they were committing a treasonous crime) and symbolic: to show England that they were beginning to identify themselves as Americans, not British subjects.

On reaching the pier, they divided into three groups and several men took charge. No one knew the names of their co-conspirators, nor did they know the names of the other commanders besides their own. They boarded the ships and demanded the keys to the hatch from the captains. The men were under strict orders to cause no harm to anyone and to carry out the rebellious act in an oxymoronic orderly fashion. Soon the chopping of boxes could be heard on the sleeping ships. The chests were torn open and the contents thrown into the Boston Harbor. Tea leaves scattered everywhere.

Some of the patriots tried grabbed up some of the loose tea and stuffed it into their pockets for their own families and personal use. The Sons tried to stop them, but at least one man managed to escape their custody and run through the crowd with his pockets stuffed with tea, even though each person either kicked or hit him as he passed by. Another man, much older, was seen filling his hat with tea, but the Sons grabbed his hat and wig and threw them overboard. Because of his age, he was allowed to escape.

No one was hurt, and aside from the tea, the only damage recorded was one broken padlock. The ships and their crews were unharmed and the Sons of Liberty pulled off the organized protest without being injured or arrested except for one man. Just as quickly as they had come, the men were gone.

| We then quietly retired to our several places of residence, without having any conversation with each other, or taking any measures to discover who were our associates; nor do I recollect of our having had the knowledge of the name of a single individual concerned in that affair, except that of Leonard Pitt, the commander of my division, whom I have mentioned. There appeared to be an understanding that each individual should volunteer his services, keep his own secret, and risk the consequence for himself. No disorder took place during that transaction, and it was observed at that time that the stillest night ensued that Boston had enjoyed for many months.4 |

In their wake lay almost 100,000 pounds of tea, worth 9,000 pounds sterling, or almost $1.5 million in today’s money.

This act became known as the Boston Tea Party.

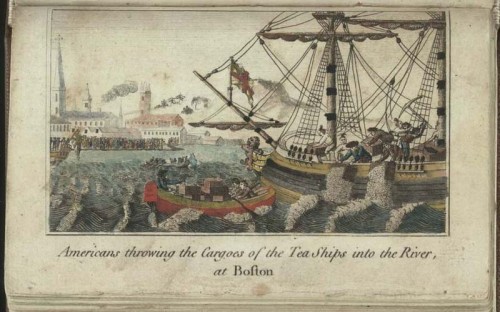

Boston Tea Party engraving by W.D. Cooper in his book The History of North America from 1789 | Public domain image.

The following morning, boats were sent out to beat the remaining floating tea down with paddles until it was completely drenched and unusable.

Who Was Involved in the Boston Tea Party?

The most well-known name involved in the Boston Tea Party was that of Paul Revere. However, several other participants were noteworthy.

Samuel Cooper, just 16 in 1773, would go on to become a major in the continental army and fight numerous battles. George Hewes, age 31, had been injured in the Boston Massacre after being struck by a rifle. He led one of the parties and wrote an account of the raid …

| It was now evening, and I immediately dressed myself in the costume of an Indian, equipped with a small hatchet, which I and my associates denominated the tomahawk, with which, and a club, after having painted my face and hands with coal dust in the shop of a blacksmith, I repaired to Griffin’s wharf, where the ships lay that contained the tea. When I first appeared in the street after being thus disguised, I fell in with many who were dressed, equipped and painted as I was, and who fell in with me and marched in order to the place of our destination. (The Boston Tea Party Historical Society, from which we obtained this quote, has extensive information on the colonial raid.) |

George Hewes was rejected as a soldier and did not fight in the revolutionary war. Thomas Crafts, Jr., however, another participant in the Boston Tea Party, became a member of Major Paddock’s famous Paddock’s Artillery Company and attained the rank of colonel in the continental army.

The patriot organization, the Sons of Liberty, provided the most participants that November night. It’s also fascinating that of those involved in the protest whose ages are known, two-thirds were under 20 years of age.

Final Comments

The Boston Tea Party was an act of rebellion from which the strained relationship between Britain and the colonies would never recover. The captains of the three ships were summoned to the privy council, but were unable to identify any of the people involved with the Boston Tea Party. The Coercive Acts (or “Intolerable”) acts followed swiftly to punish the colony of Massachusetts. The British closed down the port with the Boston Port Act until the city of Boston paid the damages. and within a year the Americans would convene the first Continental Congress to organize the protest against Britain.