Thomas Paine is the epitome of “the pen is mightier than the sword.” It was the words of Thomas Paine that fanned the flames of revolution and drove the colonists to rebel against England.

Thomas Paine, copy by Auguste Millière, after an engraving by William Sharp | public domain image, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Early Life

Born in rural Thetford, England in 1737, he went to school even though compulsory education was not established yet. His father was a corset-maker, and young Thomas was apprenticed to him at age 13 when he failed out of school. He enlisted in the Navy and served as a privateer for a short time before returning to his father’s business.

Thomas Paine established his own shop in Kent before marrying Mary Lambert. Things were just looking up for Thomas before disaster struck in the form of his business collapsing and his wife dying in childbirth.

Thomas Paine, by Matthew Pratt in 1785-95

Public domain

Having gained and lost two different positions and working as a stay-maker (making bone stiffening strips for corsets), Paine eventually landed a job as a teacher in Sussex. He married his landlord’s daughter Elizabeth Olive in 1771.

It was here that Paine first became involved in government, primarily in small civic matters. He joined a vestry (Episcopal church organization involved in secular affairs) who were responsible for collecting taxes and distributed tithes to the poor as well as joining excise officers in requesting better working conditions and more pay from Parliament.

It was also here, in 1772, that he published his first pamphlet, The Case of the Officers of Excise. A few years later, he was fired from the excise service and a tobacco business he had attempted to start failed. He was so deeply in debt he had to sell his household possessions. The same year he separated from his wife and moved back to London where he met Benjamin Franklin.

Move to America

A man of many talents, Paine is responsible for the design of several bridges in England and America, and his Sunderland Bridge has famously been copied multiple times. He received a patent for the single-span iron bridge. As well as dabbling in architecture, he developed a smokeless candle and collaborated with another inventor John Fitch to develop a steam engine.

A letter of recommendation from Franklin in hand, Thomas Paine emigrated to Philadelphia that very same year. He very nearly didn’t make it. The voyage was struck with typhoid fever. When he recovered, he got a job as the editor of Pennsylvania Magazine.

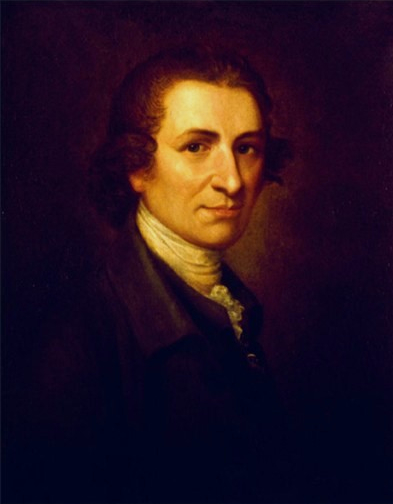

Thomas Paine’s most popular and famous work is Common Sense: a pamphlet that won him the title “The Father of the American Revolution.” It was published anonymously in January 1776 under the mysterious title “An Englishman”. It was a smash, spreading 500,000 copies all over the colonies.

Scan of the cover of the original pamphlet Common Sense.

Public domain image, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Contrary to popular belief, Paine did not write any novel or original ideas down. Rather, he broke down the complicated idea of liberty and presented it in an easy to understand format. He played on the growing frustration of the people and drove them to look to their own futures. Common Sense has been called “utopian,” written with the idea that once liberty came, the rest would follow and everything would be better.

It scared the loyalists and even some of the members of congress, but the positive influence was much more lasting. The idea that common folk could, and did, have opinions that mattered and made sense was sensational.

“These are times that try men’s souls” is perhaps his most famous quote and came from his second pamphlet. The American Crisis was meant to be an inspirational writing and General George Washington had it read aloud to his soldiers.

The year after his pamphlets were published, Thomas Paine was offered a position as secretary of the Congressional Committee on Foreign Affairs. Two years later, in 1779, following some conflicts, he made statements regarding negotiations with France got him fired in 1779.

Time in Europe

In spite of this, he was allowed to go to France with John Laurens to procure a loan. New York rewarded his political services by giving him some land. Even George Washington put in a good word for him and convinced Congress and the state of Pennsylvania to give him some money.

After the war, Thomas Paine found work as a clerk and he returned to London in 1787. Not much is known about his life until the outbreak of the French Revolution. Once again he took up his pen and wrote “Reflections on the Revolution in France.”

He was a huge supporter of the French Revolution, but he did argue that Louis XVI, the French king, ought not be executed on the grounds that he had offered so much help to America when she was struggling for her freedom.

During this time, Paine wrote and published a two-part book called Rights of Man, which was published with huge success. The British government was very angry with it and accused Paine of libel and sedition. He was tried and found guilty, but he was not executed.

Thomas Paine started losing popularity in France, and when they passed a decree in 1793 excluding foreigners, Paine was arrested. He had been living in England, but he protested that he was an American citizen, a friend of France. The American minister to France, Gouverneur Morris, ha a difficult relationship with Paine, who claimed that Morris purposely avoided freeing him and that George Washington had conspired with the French to keep him in prison.

The new American Minister did a better job at arguing for Paine’s citizenship, and he was released in 1794. He lived in Paris for a while, angry with American President John Adams for betraying France and not coming to her rescue during the Revolution.

Thomas Paine, painted by Laurent Dabos

Public domain image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

During his time in France, Thomas Paine was a friend to several controversial people who were being watched by the French government and even grew quite close to Napoleon who claimed he slept with a copy of Paine’s book Rights of Man beneath his pillow.

After discussing with Napoleon the best ways to invade England, Paine wrote several more pamphlets, but none of them reached the epic proportions of his earlier work. He eventually grew to realize how dangerously close to tyranny Napoleon had become and cooled their friendship by calling him a charlatan. He returned to America at President Thomas Jefferson‘s request in 1802.

Later Years in America and Death

His return to the states was met with the Second Great Awakening and a writhing political war. The country, being built from the ground up, was in chaos and many feared a civil war would break out between the two political parties.

The Federalist Party had attacked his works quite fiercely, and he was criticized for his friendship with Thomas Jefferson. He was terribly unpopular because of a scathing letter he had written Washington blaming him for his imprisonment in France, which had been published.

Only six mourners came to his funeral when he died in 1809 at age 72. His legacy was greater after he passed than in his own lifetime. Such great men as Thomas Edison and Abraham Lincoln openly and publicly admired Paine and his intellect, and many under-represented groups have followed his writings religiously.

Like many other men of his time, Thomas Paine did not follow any one particular religion, but rather made up his own mind on what was true and held to it. He was against slavery and perhaps one of the first people to write that men should free their slaves.