General Daniel Morgan was a general in the Revolutionary War, a talented battlefield tactician, and a politician. He took part in two of the most important turning points in the revolution.

Early Life & Seven Years

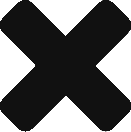

General Daniel Morgan, by Charles Wilson Peale

public domain image.

Daniel Morgan was born in 1735 to James and Eleanor Morgan in New Jersey. Both sets of grandparents were Welsh immigrants. Aside from this, little is known about his childhood, as he avoided talking about it to anyone. Most of his contemporaries assumed he had a rough childhood. Only two books have been written about him and both are long out of print. His entrance to history as we know it was as a surly teenager who ran away from home after an argument with his father.

He was mostly illiterate. He began drinking and playing cards and frequently got into fistfights and made trouble with the law for not paying his gambling debts. He was a big man, six feet tall and brawny, and he held several hardworking jobs including soil preparation for farming, superintendant of a sawmill, and a wagoner (he drove wagonloads of supplies across mountainous terrain to settlers). This last job earned him the nickname “Old Wagoner” from his soldiers when he used his wagon to help the British during the French and Indian War.

His naturally abrasive personality irritated one British Lieutenant who struck him with the flat of his sword. Morgan, the brawler, knocked him out with a single blow. He was court-martialed and sentenced 500 lashes. One of his favorite stories to tell in later years was that the British miscounted and gave him only 499 lashes and they owed him another lash. This punishment had been known to kill lesser men, and the lieutenant publicly apologized to Morgan.

He joined the British army after this as an Ensign, the only rank available. He was ambushed taking a dispatch to his commanding officer. His escorts were killed, but even though he took a bullet to the back of his neck that knocked out several teeth on his left jaw and exited through his cheek, Daniel Morgan survived. However, he carried a bad scar for the rest of his life. He spent the rest of the French and Indian War fighting against the Indians on the frontier and learning their guerrilla tactics.

His life balanced out when he formed a common-law union with Abigail Bailey and bought a farm, which he called Soldier’s Rest. The couple had 2 daughters, Betsy and Nancy. Both married Revolutionary War veterans. Daniel and Abigail eventually married in 1773.

American Revolution

By the time the Revolutionary War began, Daniel Morgan was 40 years old. Congress formed ten rifle companies in Pennsylvania and Virginia, and Morgan was captain of one. He had become proficient in Indian fighting tactics, and was an excellent marksman with a rifle. These rifle companies built up a fearsome reputation for themselves, fighting in the shadows and shooting from a distance rather than lining up and using muskets like the British.

Invasion of Canada

He was assigned to Benedict Arnold’s invasion of Canada. Morgan led the advance in indian attire. “Betwixt every peal the awful voice of Morgan is heard, whose gigantic stature and terrible appearance carries dismay among the foe wherever he comes,” is how one of the soldiers described him. After General Montgomery was killed and General Arnold was injured, Morgan took command of the troops until he was forced to surrender and was taken as a prisoner of war.

Saratoga

Surrender of General Burgoyne by John Trumbull. Col. Morgan is shown in white,

right of center.

After eight months, he was freed under the condition that he would not fight against the British until the Americans released British soldiers of war. His actions in Quebec earned him a promotion to colonel and he was given a special light infantry of backwoodsmen like himself, meant to defend the riflemen in close combat. They really shone during the Saratoga campaign. Sent north to strengthen General Horatio Gates‘ position in Albany, they saw action near Freeman’s Farm.

Morgan directed his troops with turkey calls and they surrounded the British troops. The riflemen specifically targeted the officers (considered dishonorable) and gunners manning the artillery. Their harassing the British troops and killing officers, according to British General Burgoyne, eventually led to mass desertions of soldiers and Indians and forced British surrender. In his report to Congress, Gates declared that “too much praise cannot be given the Corps commanded by Col. Morgan.” Many historians believe he did not get the credit he deserved for his actions there.

In spite of his excellent performance, one light infantry assignment was given to General Anthony Wayne instead of his own special forces. He was also passed over for promotion to Brigadier General. He took this very personally and resigned from the Army for almost a whole year. He was offered command of the Southern Theatre of the war, but he declined because Congress did not offer a promotion with the post. He stayed in retirement until he was asked to join the southern campaign against Lord Charles Cornwallis following General Gates’ defeat in Camden, SC. He put aside his personal feelings and agreed. Eventually, Congress did promote him to Brigadier General.

Battle at Cowpens

Daniel Morgan’s reputation preceded him. When General Nathanael Greene sent him to flank General Cornwallis, Cornwallis sent Banastre Tarleton‘s infamous Tory Legion in pursuit. Many soldiers wanted a crack at Tarleton, and Morgan was happy to have his turn. He chose to meet the British soldiers at Cow Pens, a cattle pasturing area in South Carolina. Morgan’s previous experience with the British gave him a significant advantage over the Tory Legion, because he knew how they would react. He also knew the terrain better. Morgan and his men camped on the battlefield the night before, and he wandered among them shirtless so they could see the scars from his flogging, promoting anti-British sentiment.

On January 17, Morgan separated his men into three lines of defense. He divided his militia into two groups, expecting they would run, and positioned them behind the crest of the hill. They were to fire twice and then retreat behind the Continentals 150 yards back, who were braver and would not run. He hid his reserves, the cavalry, knowing that Tarleton would attack head on.

Thanks to a mistaken order, the British pressed forward, and seeing the retreating militia, believed they had won. The hidden cavalry surrounded the British and the British surrendered. “A more compleat victory never was obtained,” exclaimed Morgan following his success. Many call this battle at Cowpens his “tactical masterpiece.” It was also his last major battle, as he retired shortly afterward due to a severe back pain, most likely sciatica. But he was happy in the knowledge that he had played a decisive part in the two most important moments in the war: Saratoga and Cowpens.

Politics & Final Years

He came out of retirement to help General George Washington suppress the Whiskey Rebellion. He also served in the House of Representatives and sat one session on Congress. He died in 1802 at the age of 67.