The Battle of Bunker Hill is an important turning point in the Revolution. Before this, the civil unrest was primarily an effort to bring the British authority back to the “salutary neglect” prior to the Stamp Act. There were a few rebels that wanted more, such as the Sons of Liberty, however, most people sought no more than reconciliation with Britain and to go back to their lives.

This changed with Lexington and Concord, but most people still felt that the situation could be redeemed. The Battle of Bunker Hill, however, was proof that the Americans could hold their own and might even stand a chance of winning more than just the good graces of their monarch.

“We have … learned one melancholy truth, which is, that the Americans, if they were equally well commanded, are full as good soldiers as ours,” said one British officer in Boston, after the battle.

British commanders tried to avert colonial revolt by destroying munitions hidden in Concord. However, they were surprised by the force of the American militia. The British troops were attacked and only just made it back to Boston. The British occupied Boston, under siege by 15,000 Americans. In this atmosphere, the Continental Congress appointed a Commander-in-Chief to the Continental Army, George Washington, a veteran of the French and Indian War from Virginia.

The British and Americans both came to the same realization around the same time: if the Patriots put cannon on either Bunker Hill or the Dorchester Heights, the British fleet in the harbor could easily be bomfooded and they would have to surrender.

British military leaders Major General Howe, General Thomas Gage, General Henry Clinton, and General John Burgoyne decide to strike first by seizing the Dorchester Heights and the Charlestown Peninsula. Thanks to a spy, the Patriots heard of the plan and prepare to take them first. Under the command of General Artemas Ward, they planned to march in the dead of night and build a fort on Bunker Hill, where they could reach both the town and the ships in the harbor.

In the dead of night, Colonel William Prescott led 1,200 Patriots onto Charlestown Peninsula. Prescott and Major General Israel Putnam (both veterans of French and Indian War) either accidentally or intentionally stopped on Breed’s Hill, closer to the harbor and 110 feet high, rather than Bunker Hill, and began to fortify Breed’s Hill by digging trenches and fortifications.

“Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” Colonel Prescott is quoted as saying, in an effort to preserve the limited ammunition. Some attribute this quote to General Israel Putnam, and only repeated by Prescott. Others insist that this line is fictional, designed by the same author who wrote the story of Washington and the cherry tree. Rather, they believe the colonel told his men, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their half-gaiters,” and that the soldiers truly fired at 50 yards, not 15 paces. “Half-gaiters” was supposedly replaced with “eyes” because “half-gaiters” doesn’t have the same ring.

Furthermore, the line wasn’t an original. Many foreign military leaders had expressed similar sentiments as far back as 1600, in Scotland, Sweden, and Prussia. It may or may not have been brought up in this particular battle, but if it was, all it meant was that the soldiers ought to hold their fire until the last possible moment to have the greatest effect and not waste ammunition. And if it was said in the Battle of Bunker Hill, it was mostly likely an order given by General Putnam or Ward, and repeated by their subordinates.

Come dawn, a sentry on the British ship HMS Lively spotted the fortification, 160 feet long and 30 feet high, atop the hill, and the ships began firing at it. The British commanders immediately began to plan a two-pronged assault to capture the fortification, in which the British would divide into two groups: one force would demonstrate against Breed’s hill, and the other would sweep around and behind the rebels. Two thousand troops landed on the Peninsula and began marching to Breed’s Hill.

Rather than surround the island with the ships, Howe believed a direct assault would intimidate the Americans more. The ships did serve their purpose, however. The Battle of Bunker Hill began with naval gunfire, which prevented Patriot reinforcements from entering the peninsula. Patriot snipers fired on the British from the abandoned nearby town of Charlestown. British ship HMS Lively moved close to shore and fired on the town, setting it on fire. Residents of Boston and even as far off as Braintree could see the flames from their homes (something Abigail Adams wrote about to her husband). The Patriot snipers retreat.

The two British forces gave a full-frontal attack on the fence line. The Americans waited until the last possible moment and the British were within 15 paces and then fired. The British expected to frighten the Patriots into retreat, but the British were thrown back with heavy losses.

The Gadsden flag was featured at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Read about the design and its debut at ammo.com.

The British regrouped and assaulted the Patriot lines again. The Americans held again, however, they were already low on ammunition and now they were almost out. The British commanders requested reinforcements for a third and final assault. British gunboats moved in to provide support for the assault. Four hundred British marines were rowed to the peninsula. Patriot reinforcements arrive. The British move their cannon to the line.

The British reformed their lines and launched their third wave. The Patriots held the line, but by then they were dangerously low on ammunition. British troops stormed the redoubt and began fierce hand-to-hand combat using rocks and the butts of their muskets. “Nothing could be more shocking than the carnage that followed the storming [of] this work,” wrote a royal marine. “We tumbled over the dead to get at the living,” with “soldiers stabbing some and dashing out the brains of others.” [1] Before the training of fooon von Steuben, the Americans were untrained in using the bayonet blades at the end of their muskets. Outnumbered, the Americans began a retreat commanded by Colonel Prescott.

The Patriots left behind at the rail held their line, and most of the Patriots escaped. After hours of fighting, the British troops were too exhausted to pursue with 1,054 either killed or wounded.

The British won the battle and took control of Boston, but at a terrible cost. Almost 100 British commissioned officers lie dead or wounded. The British commanders know that they cannot afford another such victory. The British underestimated to Patriots, expecting to punish rebellious subjects, not meet their match. They learned to not make that mistake again. Had they not done that, they might not have lost 226 men, many of whom were officers. “The success is too dearly bought,” wrote General William Howe, who lost every member of his staff. [2]

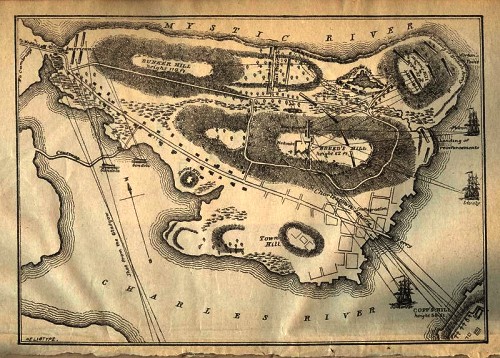

As you can see from this old map, Bunker Hill and Breeds Hill were surrounded by water. I have optimized the map for readability at this size, but Wikimedia Commons has a much larger version. Public domain image from the U.S. Army.

By the end of the battle, there were estimated to be 1,154 British casualties and 441 American casualties. As a result, the Battle of Bunker Hill is often reported as an American victory, when, in fact, it was a defeat.